In 2004 I culled my sketchbooks in search of drawings that incorporated tools alongside pottery, mostly mine. “Tool” was broadly defined. It included any instrument or device that had a specific and recognizable shape for a particular task—perhaps a pair of vise-grip pliers, a compass, a chair, or sharpened colored pencils. For me these tools served as reference points within each drawing, because their presence calls forth the crisp mental images we all have of such common objects. In this way they clarify the inherent spirit of both the drawing and the actual pot.

Chinese Swivel Stool, h 14" w 10.5"

pen, ink, acrylic collage

These drawings began as a habit, to capture my perception of what was in front of me. But as I amassed the more powerful examples, I discovered that drawing was just like my favorite screwdriver. That tool, with its bright orange plastic handle, is stored on our kitchen counter among the scissors and pens by the weekly calendar. It has interchangeable heads of varying sizes so I can use it on a regular wood screw, a Phillips head, or a star screw. The tool of drawing is similarly versatile. When embarking upon a new series, I have often switched the "tool-head"—from pencils to water-soluble pens to Sharpies to crayons.

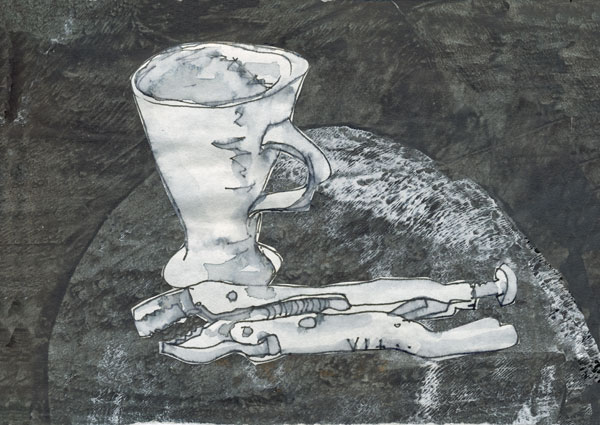

Vise Grip Coffee, h 6" w 8"

pen, ink, acrylic collage

When I am studying the outline and volume of an object, the tool of drawing allows me to drill down to an essence that encapsulates that moment's perception. Drawing clarifies shifts both in perspective and in the aesthetic choices I choose to make about form. Respecting the wiggles and imprecise gestures of my hand, these collages become a catalog of the views that enrich my life as well as a source of freshness in my claywork. Every drawing takes a sip from the cup of risk, but within the confines of a spiral-bound book there is no danger, just uninviting paths. In contrast, the energized drawings create stepping-stones from my imagination outward to pottery that will take its place in the external world. Drawing repeatedly teaches me not to make assumptions about what I see. Sitting down at the wheel, it reminds me not to throw by rote. I have to forget the name of the thing in front of me to permit the eye and hand to work intuitively, guided by observation not by assumption.

Panes of Grass (detail)

h 12" w 8.5"

pencil

Drawing meshes into many crannies within my working process. There are sketches that deal with inklings of new forms. Preliminary to glazing, there are sketches that explore how brushwork will respond to curve of a plate. And then there are drawings of finished pieces embedded in useful life. As an artistic tool, such drawings allow me to ponder context and use, slowly but surely guiding me into the next cycle of claywork. I draw in short segments, usually ten or twenty minutes at a time. When I was working on the images of tools, I set out to make thirty images. I trust in the idea of accumulation.

Soup and Cup, h 6" w 8"

pen, ink, acrylic collage

A series might last one month or so: a stacking-up of chairs with pots, or pots with shadows, or cups and bottles with contrasting hard-edged commercial containers—a Campbell’s soup or a Coca-Cola can. I favor projects that have a tight framework, because they are self-motivating; I also call this the “teaspoon” method. Every day I will make one more ratcheted turn of the drawing screwdriver. I don’t have to rethink the process or question the direction I’m headed. I grab the drawing-tool-of-the-day, arrange perhaps the chosen wavy-necked bottles amidst an elongated hammer, and sit down to draw. When I borrowed a selection of distinctive hammers from a blacksmith friend, each “automatic” drawing session sought out the line between shadow and negative space. With the hammers I conceptually enjoyed the contrast between the implied action of pounding and the potential fragility of the pots.

My many drawing sketchbooks are linear only through the chronology of making. Some ideas are revisited. Others hopscotch, the germ of an idea in one notebook becoming the basis for an entire series in another. Each page has its own presence. I take aim with an idea, but try to strike a balance between blindly making marks and working within the (limitless) confines of a strict concept.

Garlic Stem in Moon Vase, h 9.5" w 9.5"

pen, ink, acrylic collage

The drawing tool can even call attention to what is happening outside the frame. Winter snowstorms provoked a dramatic lesson in understanding calligraphic line by simplifying the landscape, allowing only the toughest stems to stand proud of the snow-covered ground. I saw each stalk isolated as if it were a graphic line, and so drew them with my homemade brushes. These drawings led me to see how a simple yet specific motif of grass could reflect the changing seasons—from the energy of emerging looping onion grass in spring, to the languorous fleshy stems of summer, to the extended survival of fall flower heads and the withered resilience of stiff grasses withstanding winter winds.

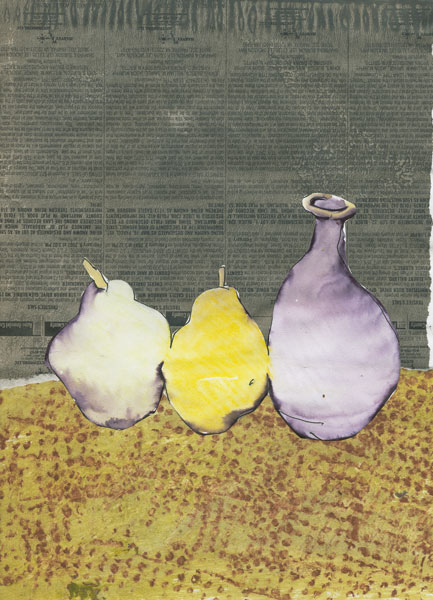

Pear Shapes, h 12" w 8.5"

pen, ink, acrylic, newspaper collage

I always have a sketchbook, but it isn’t precious. There are scribbled phone numbers, sketchy drawings of whatever is in front of me, lists of tasks, and intriguing quotes. If I dream of a form while waiting at the doctor’s office, I can pencil in the silhouette. On a museum trip I can visually jot down historical inspirations. Travelling in Japan, I loved the small museums with cases of shards. Attracted to the remnants of pottery, I made drawing after drawing. This grist was handy when I was working towards an exhibit and found that many pots were splitting along the rim because my new slip was too strong. Remembering all those sketches I thought, “why not turn these struggling bowls into shard plates?” I snapped the rims and found freedom in a new solution I’m still exploring.

Cocoon on School Chair, h 14" w 10.5"

pen, ink, acrylic collage

In my studio I have low windows facing a wide farm pond. For years I let the grass grow tall in front of those windows. As I gazed out, I loved the way the tall grasses intersected the individual panes of glass. Out came my favorite tool; I made many drawings of those grasses as inspiration for plates. The lower panes/plates were full of vertical lines while the upper panes often had only one seed head. That kind of framing—discovered by drawing—led me to contemplate the plates as if I were looking through a zoom lens. In the field, zooming in requires laying on your belly examining the stems a few inches in front of your nose. That’s how I discovered the weedy spring onion grasses that loop as they grow. Those became another inspiration for distillation into many series of unique plates.

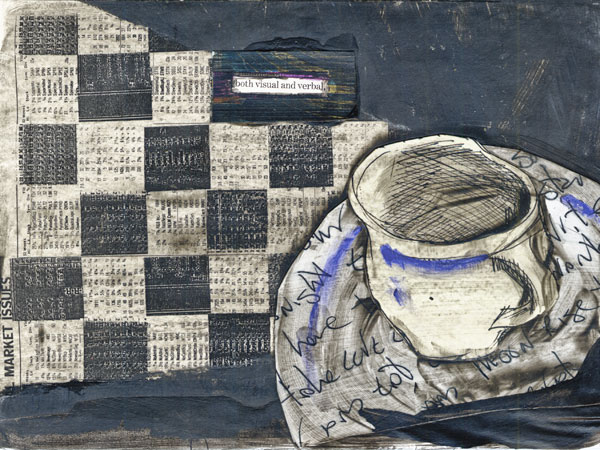

Visual and Verbal, h 6" w 8"

pen, ink, acrylic, newspaper collage

Many potters launch themselves from Hamada’s shoulders; he talked of repeatedly drawing a sugarcane pattern, repetition birthing fluidity and a lack of self-conscious line. I started there as well, but over time I realized it was more vital to really look at the grasses in my field. Drawing the character of actual stems in my loose way has become far more fruitful than abstracting one generalized pattern from many nuances. Just as each tool has a distinctive use, so does each subject and each drawing.

As a tool, habitually drawing on paper creates practiced solutions and flexibility, leading to a spontaneity derived from looking, thought, and understanding. A passionate drawing of objects leads to intriguing and evolving tensions between one’s hand, one’s vision, and one’s materials.

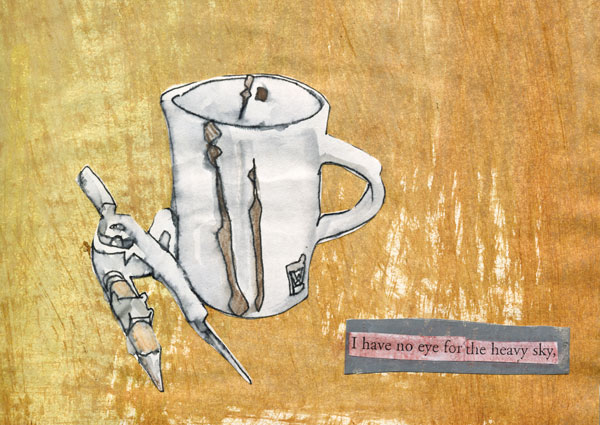

Compass and Cup, h 6" w 8"

pen, ink, acrylic collage

Consider, h 6" w 8"

pen and ink