Spiralling Choices

[Published in The Log Book, #20, 2005]

[additional images provided here]

I remember when I first met Rob Barnard at his studio in Timberville, Virginia. Next to his small board and batten studio in the Shenandoah Valley, he had a beautiful whale shaped anagama surrounded by rocks and oak trees. It seemed so minimal and direct. At first, I thought I could never work like this—with one clay, one kiln and no choices of slips or glazes. But his spirit infected my dreams. I began to see that when I used decoration on my work people paid attention to the surface, but not to the form and expression of the pot. I began to get inklings of how to work with a minimal palette that opened up huge fields of creative answers to aesthetic problems.

Soft Smooth Bud Vase, h 24cm

Catherine White

Stoneware fired at the kiln rear lying on sand

Thus, the first and fundamental inspiration I drew from woodfired pottery, in 1984, was to strip my work of added decoration by choosing to work in a white clay with a gas-fired clear glaze. My aim was to apply to this glazed ware the simplicity and directness of a woodfired aesthetic—avoiding any decoration that might obscure the expressiveness of form. An elemental texture of feeling seemed achievable through the touch of my hand, as well as through the visual lines and volumes of a shape.

Faceted Vase, Catherine White

As my glaze work evolved I added layers, obtaining depth and variation by irregularly applying a crackled white slip and a thin celadon glaze to a light colored clay body. Through all these years my woodfired work proceeded in parallel, recentering my vision towards spareness, towards the elimination of superfluous flourishes, towards a somber palette of clay, color and form. Balanced on edge, both the dryness of woodfired ware and the restlessness of crackled and dripped layers force the user of pottery to be creatively attentive. Thus, woodfired or glazed, my pots ultimately are portraits of form that express themselves through use. Physical use is an essential component of the aesthetic experience of pottery. My job as an artist potter is to go beyond the pigeonhole of function. It is important to push the boundaries of idea and metaphor, playing with the balance of certainty and risk.

Golden Shell Cocoon, Catherine White

Stoneware, h 15cm

Fired in front stack closest to firebox

As I worked in Iowa in August 2004 with an international group of potters who were passionate about woodfiring, we constantly threw labels around about ash, clay, reduction, the use of local materials, backpressure, coals, and stoking. But until we actually rubbed shoulders within the same experience we didn’t know if our words were equivalent. Our conversations about our home kilns and the pots we admired swam in large nonspecific circles. I wished I could put on weights like a scuba diver and drop to the bottom of the surrounding oceans of metaphor to discern the foundation structures of each of our formative experiences. I am afraid as potters that sometimes we are following in the footsteps of best-selling authors. With these authors the more they repeat themselves—people like John Grisham, Mary Higgens Clark, or Tom Clancy—the more we reward them. Consistency leads to better sales is the lesson. Let people know what to expect. Be a brand. Without realizing it we are imposing restrictions on our own creative options through our lack of insight.

Meandering Line Torso, Catherine White

Low iron Stancills stoneware, h 21cm

Fired along sidewall, kiln middle

It is all too easy to say “I am only a functional potter or china painter.” We need to examine our reasons and our touchstones as we make woodfired ceramics. We need to leave behind the blinders of financial success, gender, or nationality. We must wake up and push the creative edge of our pigeonholes. I must remind myself to look ever more closely at the balance of clay body choices and firing choices. We don’t make pottery in order to be boxed. Potters tend to be individualists, yet as tender human beings we must go beyond exhibiting only assertiveness in our work; we must also represent our vulnerabilities. We need to combine ambiguity and clarity in the base of a bowl and understand the possibility of transformation and repose through the use of our forms. We have to remember the role model of those prolific artists who thrive on uncertainty, economics be damned. I would love to push our field beyond the conventional pigeonholes of drippy glaze effects, encrusted surfaces, or supposedly pure function—towards a dance of risk amid experience.

In my work the total combination of each element of clay, firing, form, and use is significant. I seek a tensioned equilibrium among them all. Conceptually it doesn't matter whether work is wood fired or not because I am adjusting the nuances of both techniques to fit a unified feeling. The wood firing is a means to an end. Yet, it has become an indispensable variable tool that tensions the intent of my hands with the influences of nature.

Red Trumpet Vase, Catherine White

I feel that there are two basic approaches to ware placed in a wood firing kiln. One is to use the wood as a heat source that subtly adds an irregular flashing of color to the glaze and/or clay body. Another approach is to use the wood for a more vigorous, flame-applied effect. For me, it is the irregularity, subtlety and uncertainty of the second approach that encourages intriguing work. I am energized by the directness of the method. I bring intent to my forms, intent to the way they are placed in the kiln and intent as to how the kiln is fired and cooled. The relationship of stacking to form is an important consideration in the woodfiring dance. I think of stacking the kiln like solving a three-dimensional puzzle. There is a given size of kiln and a given set of shelves. I (almost always) choose not to glaze or slip the work in the kiln. I thrive upon a large variation in temperature from front-to-back. In the front it is hot and the ash gets drippy and crusty, while in the rear effects are more soft and subtle. I make specific work attuned to the results of the different sections of the kiln. I need a full repertoire of shapes to obtain a beneficial interaction. The variety helps to alter the flame as it moves through the kiln, like different size boulders adding turbulence and pools in a stream. It causes the momentum of the flame to be shifted and drawn throughout the stack, leaving a varied palette of markings. Sometimes a given commission or idea will drive the stack—like one large flower container—requiring differently sized forms to be created for the stacking, thus usefully altering my usual assumptions and relationships. Technical questions can drive new aesthetic solutions, keeping the work alive.

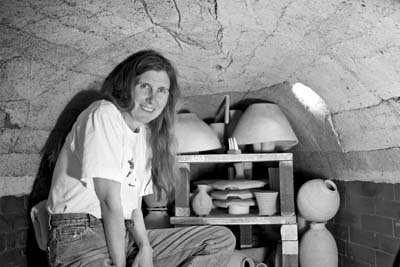

Catherine stacking the rearmost shelf

In my mind, kiln building, like house building, is a necessary evil. When I am making pots I work in series and usually by the third piece I understand what the form requires. I hope never to have to build three houses or three kilns to understand the form although I will do what is necessary. I think of myself like a hermit crab who will crawl into an empty shell that fits, then happily inhabit it fully. In the cycle of a firing the first essential choice is the clay body. Because there is no glaze added to the work its surface is elemental to the ultimate result. I mix a large enough batch of one type of clay to make all the work necessary for an entire kiln load. With each firing I gently change my clay, adding more or less iron, using a bit more or less of local clay seasonings. Before I begin, I might look hard at a new range of old pots, making drawings of what I would like to transform. Then I wedge the clay and jump into throwing. Some days I realize I have to distrust my drawings. I can do things on paper that don’t take into account the three-dimensional aspect of gravity or the centrifugal force of the wheel. I act on an idea, but progress based upon what my hands provide. Later, I will have to act upon what the kiln fire produces, adjusting clay, form and stacking in the next cycle.

Large Torso Jar, Catherine White

Low iron Stancills stoneware fired just behind the firebox

Once I decide on a form—perhaps small vases—and a number—like eight—then I throw until they are done. Music keeps me going so that I don’t stop and get too critical at this phase. In attitude I pretend to enter the stream of work as if I had already made four hundred pots. I endeavor to build on the momentum of the last firing, yet simultaneously seeking to avoid mere repetition of prior successes. Searching for the heart of expression I amplify shapes and exaggerate what was just a twinkling idea of form, surface or use. Through it all I look at old drawings, review my notes, and continue to draw the new work as it is thrown.

Red Rippled Bottle, Catherine White

Once all the pots are made, dried, and the firing imminent, we take the boards out to the dirt floor under the shed roof in front of the anagama. I love seeing all the work lined up, silent shapes full of potential. Then Warren and I perch on child-sized chairs in the kiln as we carefully and mindfully stack. How the kiln is stacked determines the ash deposited an each piece, making or breaking each pot. I have learned to take my time with this step. Slowness here is essential. We take many breaks for tea, stepping out of the kiln, contemplating what pieces go next, perhaps according to plan or newly improvised. We eat good lunches and don’t rush or work too late. I am glad for the discipline a school age child provides. I work until 4 pm when the bus drops off my daughter. I have to stop then and pay attention to her life, make dinner and do whatever chores are called for. It gives me perspective and I can refresh my eye before the next day of work. We take three days to stack the kiln with a day off before we fire. The day off gives us essential time to stretch our backs, provision the larder for the incoming hordes, and to rejuvenate before a three-day firing with a select group of helpers in and out of the house and up at all hours.

Lined Sphere Vase, Catherine White

After the firing and unstacking there is a stretched out judgment as to what works and what fails. This honing happens throughout the full, spiraling cycle of making, firing and using pottery. Not only are conscious choices in the clay palette, stacking, wood and type of firing essential elements in the entire expression of form, but also physically using the work is instrumental to enlighten the next round of making. As an artist I wish to avoid being stagnant. I think of making pots as a discipline similar to writing poetry. I recombine the language at hand to derive new combinations that express my deeply held emotions about the surrounding natural world. I must build on ideas, history and changeable aspects as my vision evolves. As I resolve one problem—the aesthetic nuances interwoven with the technical—I eagerly approach the next cycle of uncertainty, hope and change.

Anagama front

Kiln side view (with Warren)