Instructions for Failure

[Published in Studio Potter, V39 #2, pp 6-11, 2011]

[With some additional images]

Success is nothing to sneeze at but failure, too, offers great possibilities…. We have all sorts of negative notions about failure and so the hidden message is don’t risk anything. Don’t take chances. Be a good boy. Stay within the limits…. But of course in the arts and virtually anything else that leads a satisfactory life, failure is implicit. You try things, you fall on your face, you figure out what went wrong, you go back and try them.

— Jules Feiffer (as interviewed by Jesse Rhodes; Smithsonian, September 2010)

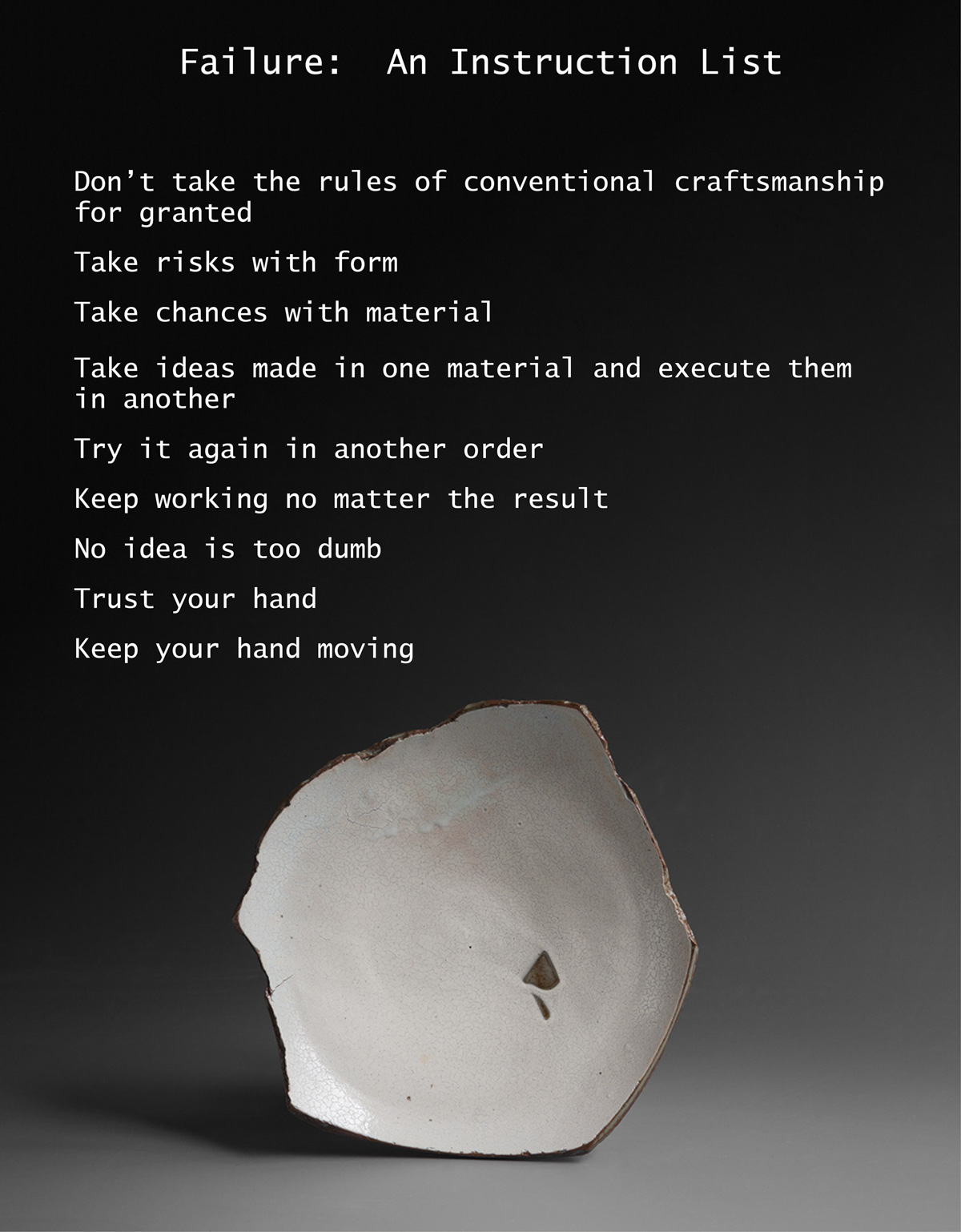

Shard Plates (set), 2008, Catherine White

example: h 2.5" w 9.5" d 9"

When I first started a studio with my husband, I decided to work without decoration in a clear-glazed white clay so that form and surface would speak as one. Those first white pots are timid in their gentle attempt at rebellion. On that early hesitant artistic path I began to work against notions of perfection. One approach was shifting materials. I added a friend’s wild Vermont clay that imparted a naturally irregular mix of quartz and feldspar rocks along with a touch of sand. I was trying to throw classical forms with unrefined materials, pushing my hand to find a tension between elegant and rough. My old studio mate looked at the work and said, “Galleries aren’t going to like those rocks; that’s not going to be saleable.” But I was fixated on working with a child’s nonchalance, an attitude that for me was a source of rebellion—an opportunity to break the rules, accept the flaws, and reach for those quirky aspects of human aliveness that we treat as personality, not as defect.

White Bottle, 1984, h 9.25" w 3"

Tilt Bottle, 2006, h 10.75" w 3"

Catherine White

When I began a series of faceted pots I liked how the grit broke up the surface. I often would catch a rock and cut through the wall of the pot. I remembered seeing an antique amber-glazed Korean faceted jar. The potter had cut through the wall and simply slapped the faceted slice back on the wall as a patch. The spontaneous caress in that motion had been sealed by the glaze and fire, and I wanted to capture that energy in my work. I remember showing images of these pieces and being asked—or told— “I assume that at some point you’ll get better and won’t cut through the wall anymore.” My response was, “Well, then it will be time for me to move on and find a more beautiful way to fail.”

White Faceted Bottle, 1992, h 9.5" w 6"

Catherine White

Teapot with Patch, 1992, h 3.75" w 5.3" d 3.5"

Catherine White

As my work progressed I moved away from porcelain and into a grey stoneware. I began to add a white slip over my clay so that my palette had a depth and variety of grey-whites. At the beginning of this pursuit the bone-dry clay was fragile and the crackled slip strong. At one point, getting ready for a firing, I found that in the bisque kiln all of my rims had cracked. It was a warm day and as I unloaded the kiln I lined up the pots outdoors on the gravel. I leaned against the studio’s board and batten siding and thought about giving up—or—could I remind myself that there are no mistakes in art and find the beautiful tension in this work? I remembered that when I traveled to small museums in Japan I was often drawn to the cases of shards. I had made many drawings of the remains of old, broken pots. So I went inside the studio and got myself a pair of vise-grip pliers to snap off the rims. Editing the work down to an essential structure actually tensioned the graceful curves with sharp edges. They’re still among my favorite plates in use. [First article image.]

Example of a later, 2010, Shard Plate

h 3" w 11"

Catherine White

When I get ready to fire our anagama I usually choose one primary clay body to mix. Basing the evolving composition on samples from a previous firing or electric-kiln tests of unknown new clays, I get to work putting all of my energy into learning the current claybody’s oddities and abilities. One time, choosing to simplify my studio life, I took the grey stoneware from my gas-fired work and coated it with a Redart slip, hoping to get a deep red color from the anagama. Towards the end of the firing we accidentally knocked over a piece near the rear stoke hole, so we reached in with tongs and stood the vase back up. At the same time for fun we pulled out one of my Redart slipped vases. Fast-cooled, the surface was a shiny green glaze, not the desired rich, reddish-brown matte. Depressed, I told a colleague and he said, “Well you can always sandblast all the pieces.” By providing a back-up plan—as lame as it might have been—to counterbalance wasting all that effort of making and firing, his comment improved the sleep I got over that week of cooling. When we unstacked, there were some pieces that were a beautiful, somber, deep black. Yes, there was much that was way too shiny for my taste, but the lesson was reiterated: keep working.

Trumpet Vase, 2003, h 10.5" w 7.5" d 5.5"

Grey stoneware with Redart slip, woodfired

Catherine White

For a recent firing I made a large series of cylindrical forms. When they came out of the kiln I was disappointed by how the fire marked the work and how they didn’t add up to what I had imagined. I took the cylinders into the studio for a rinse. Then I did a touch of sanding just to get a better feel for the surface. While I studied the piece more carefully I happened to turn and look to the left side of my sink. There was a ten-year-old cylinder with almost the identical proportions. Stuffed with brushes, it was hiding in such an obvious place that I no longer saw it with an aesthetic eye. Obviously this idea has been gnawing at my imagination for a long time. At first I felt dumb. Why hadn’t I learned the first time around that this configuration wasn’t working? But then I decided that it wasn’t failure, yet. I just haven’t figured out how to scratch this particular itch of an idea.

White Triangle Pillow Vase, 2009, h 9.5" w 11.5" d 3"

Catherine White

Another initial piece in a lineage of assembled vases

A few years ago I was one of an international group of potters who gathered for several weeks to make work and then fire an anagama before a conference. Next to a large farmed field, we worked under a big tent just like one might rent for a wedding reception. We had a generator for the electric wheels and a few funky Korean and Japanese-style kick wheels. It was an awkward arrangement for working and all of us felt out of our element. The heavily grogged clay was not to my taste; the wheel felt crudely plopped on the uneven grass; I didn’t have at hand some required tools. On the last day of wet work I finally made some bottles with potential. At five pm we turned off the generator; we had had enough of that loud beast. We all began to clean up, setting work to dry and making space for dinner. As I moved one board of pots I tripped and knocked over another board with my favorite bottles. They landed wet and squashed, face down in the grass. But I was so invested in these narrow-necked bottles that I picked them up, pulled them like handles, stuck my throwing stick inside and turned them on a banding wheel until they were organically balanced. They had a very fresh, loose, human quality. The kiln was difficult to fire, with too many cooks jockeying to tend it, yet my under-fired bottles retained an exciting energy.

Resurrection Bottles, 2006, h 7.5" & 8.25" w 2.5"

Catherine White

When I got back to my studio I tried throwing bottles and knocking them over on purpose, but I could never find the right balance. I came to realize that I needed to throw to the edge of collapse and then achieve control by hanging them upside down to straighten, pulling and coaxing each one into a wild poise.

Coaxed versions

Tall Bottle, 2006, h 14.75" w 3.5"

Bottle, 2006, h 12.25" w 2.5"

Catherine White

As I write, I am in the studio sitting in front of a table of plates. I am trying a new mix of raspberry clay, gravel dust and my hillside-ochre as printed materials in my slip. While these are my same old materials, the combinations are new and different. Part of my brain says, “Stop, you’ve done this before.” But still I have to attempt this variation in the gas kiln. Albert Einstein is quoted as saying that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again hoping for a different result. But lately I have begun to think that this is really a definition of optimism—the hope that this time I’ll alter the outcome: I’ll mix the correct combination of materials; the glaze application will be just thin enough; and the firing will achieve an admirable alchemy of temperature and reduction. It’s like being a gardener, choosing to plant an untried variety of tomatoes for the new season, hoping that this year the variables of weather, water, soil, and temperature will all collaborate to birth the perfect fruit.

Another experiment with basalt rock dust

Black Spiral Platter, h 6" w 19" d 10"

Stoneware, white slip, Vulcan rock glaze lines

Catherine White

Such repetition—punctuated by failure and success—enhances our ability to stack future artistic odds in our favor. I think ceramic artists develop an ability to foretell the future, a honed skill that artists in other media need not engage. Beginning with this wet substance, we have to understand how it dries and shrinks; how the colors shift as heat is applied. We see one object in process standing alongside its potential brethren. We can visualize impending transformations arrayed as a family of close siblings. This experiential ability provides a capacity to see the unseen, to transform failure into tomorrow’s instructions.

Failure: An Instruction List

Shard Plate, 2008, h 3.75" w 5.5" d 3.5"

Catherine White

Horizontal Quartet, 2010, h 11.25" w 8" d 6.5"

A series inspired by mud dauber wasp nests

Catherine White